|

P r o p h e t i e s O n L i n e |

|

|

The largest library about Nostradamus for free ! |

|

Don Giovanni Bosco Altre Profezie Elisabetta Canori Catherine Emmerich Suor Gabriella Gioachino da Fiore Jacob Lorber Saint Malachia Rasputin Suor Ali' Anna Maria Taigi The Archangels Maria Valtorta The Virgin of Naju

|

By clicking from the top links you can access pages relating to some very famous mystics |

|

|

|

|

|

Read my blog below, or check it online at: |

|

|

Note: All reasonable

attempts have been made to contact the copyright We would be grateful if any whom we have been unable to contact would get in touch with us.

|

|

|

Joachin Da Fiore

IOACHIM DE FLORE - SPIRITUS INTELLIGENTIAE

"In this way, three conditions of the world (tres mundi status) bear witness - as we have already stated in this work - of the symbols (sacramenta) of the divine page: the first, when we were under the law (sub lege); the second, when we were in grace (sub gratia); the third, which we expect soon, which will be of the abundance of grace (sub ampliora gratia). Indeed, as says Iohannes, the Lord 'has given us grace over grace' (Ioh.1,16), and both faith and love to our desire. Hence, the first time was that of science, the second that of wisdom, the third will be that of full knowledge; the first was of servitude, the second of childlike obedience, the third will be of freedom; the first was testing, the second action, the third will be contemplation; the first was fear, the second belief, the third will be love; the first was the time of the old men, the second of the young men, the third will be of the children; the first was under the light of the stars, the second at dawn, the third will be under full daylight; the first was winter, the second spring break, the third will be summer; the first brought nettles, the second roses, the third will bring lilies; the first gave grass, the second stalks, the third will give grain; the first gave water, the second wine, the third will give oil; the first corresponds to Septuagesima, the second to Lent, the third will be Easter. So the first condition belongs to the Father, the creator of all things, whose time begins with the beginning of history, referred to by Septuagesima, and reaches out to the apostles. If 'the first man was made of earth and is of earth, while the second man comes from heaven' 1Cor.15,47), the second condition must belong to the Son, who deigned to dress the clay we are made of, to fast and suffer in it to reform the condition of the first men, who killed to eat. The third condition belongs to the Holy Spirit, of whom the apostle says 'where there is the Spirit of the Lord there is freedom' (2Cor.3,17)." Ioachim de Flore, Concordia Novi ac Veteris Testamenti, 1199 ca. (book 5, folio 112) I hope that my wooden english translation still gives an impression of the music and rhythm of the Latin original. I put it in front because it, beyond being the part of Ioachim's work with the greatest effect on the 13th century, will probably strike a chord in many inventors of Ars Magica campaigns: it structures the world and its history in an immediate, sensual and narrative way very close to the method of a writer designing the structure of a novel, or a storyteller designing a campaign. And yet it is intended to be a key to the immediate future of Ioachim.

THE MAN - BEATUS IOACHIM ABBAS FLORENSISI will be rather thorough in this section for two reasons: First, to clarify the social position, self representation and contemporary image of an exceptional individual. Second, to give those who wish to introduce him into their campaigns sufficient background to do so without risking embarassment by some well read (read: smart ass) player. Ioachim was born 1130 at Celico in Calabria. Most biographers agree that he was the son of a tabellius, a municipal notary. In the 1150s we find Ioachim as an official of the chancellery of William II, last Hauteville king of Sicily. Perhaps 1167 he abandons this career for a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, thereby escaping his family which disapproved of his spiritual interests. (Some authors date the pilgrimage as early as 1150) "Not much later his religious fervor brought him to Jerusalem, where, along the way, he sated the poor with all he possessed. Then he took the rugged white habit of the monks. Having come to a desert, he feared to die for thirst and covered himself with sand, so that his corpse would not be devoured by wild beasts. Then, while reflecting over the meaning of the scripture, he fell into deep slumber. Lo, there appeared to him a river of oil and a man standing near it who said to him 'Drink of this river.' Thereon he drank of it until sated. When he woke up, he found that he had the understanding of all the Holy Scripture. He passed all the Lent in an old cistern on the mountain of Christ's transfiguration (scilicet: Mount Tabor), waking, praying, fasting and singing hymns and psalms." Gabriele Barrio, Joachimi Abbatis Vita per Gabrielem Barrium Franciscanum Edita, 1571. This obviously must be taken with a few pounds of salt, but gives an idea of the pilgrimage's importance for his work and image. After returning from the Holy Land, Ioachim takes up the life of a hermit in various places. Finally he lives in the monastery of Sambucina, where he begins to preach. The bishop of Cantanzaro legitimizes his preaching by making him a priest around 1170. 1171 at Corazzo a noble greek monk convinces Ioachim to take the Cistercian habit. 1177 Ioachim is elected abbot of the Cistercian monastery Sta. Maria di Corazzo. In these years he publishes De unitate seu essentia Trinitatis, attacking the teachings on the Trinity of Petrus Lombardus. 1183 Ioachim is, with business for his monastery, at the Cistercian abbey of Casamari in southern Latium. There, in the night before Easter, he has a vision. "In the complete silence of this night, and, as I believe, just in the hour when our 'lion of Juda' (Ap.5,5) was resurrected from the dead, while I meditated on 'Rapt in extasy on the day of the Lord, I heard behind me a powerful voice, like a trumpet ...' (Ap.1,10), I caught with the eyes of my mind something of such clarity of intelligence on the subject of the fullness of this book of the Apocalypse and of all the harmony of the old and new testament." Ioachim de Flore, Expositio in Apocalypsim, 1199 ca. (book 1, folio 39) Another vision follows on Whitsunday. "While I entered the church to pray to the Almighty in front of the altar, I felt in me a sort of hesitation about the belief in the Trinity. It was difficult to grasp for intellect and faith, that all these persons were one god, and one single god was all these persons. When this happened I prayed with fervor and, frightened, urgently implored the Holy Spirit, whose holiday it was, to deign to reveal to me the sacred symbol of the Trinity, through which the Lord promises us complete knowledge of the truth. Saying these things I began to sing to reach the verse for the day in the book of Psalms. At once I had in the mind the image of a psalterium (scilicet: a kind of zither) with ten chords and in this image I saw so clearly and evidently the symbol of the holy Trinity that I was brought to exclaim 'Which god is a great as our God' (Sal.77,14)." Ioachim de Flore, Psalterium Decem Chordarum, 1187 ca. (prologus, folio 227) In this time Ioachim begins to write his biblical commentaries: Concordia Novi ac Veteris Testamenti, Expositio in Apocalypsim and Psalterium Decem Chordarum. 1184 Ioachim meets pope Lucius III at Veroli. As a Cistercian monk he needs official permission to write, and gets it from the Pope. He might have been invited by Lucius III to comment on the very popular sybilline prophecies. Anyway, in 1184 Ioachim completes Expositio de prophetia ignota on this subject. Ioachim's permission to write is renewed by Pope Urban III 1186 at Genova. In Spring 1186 Ioachim leaves Corazzo and retires with a few pupils to a hermitage. The monks of Corazzo protest and claim their abbot back. In 1188 pope Clemens III frees Ioachim of his duties to Corazzo and encourages his work explicitly. At the end of the year Ioachim searches the inhospitable Sila mountains in Calabria for a place to found a new monastery. With the help of Tancredi of Hauteville he raises the funds for it, and from 1190 takes up residence there. Spring 1191 Ioachim is at Messina, where he might have met Richard Coeur de Lion. Several English chronists report how Ioachim explained to Richard the meaning of the seven heads of the apocalyptical dragon: five correspond to dead persecutors of Christendom, the sixth to Saladin, and the seventh to the antichrist itself, already born into the world. In Summer 1191 Ioachim meets the emperor Henry VI under the walls of the besieged Naples. It is told that, by exegesis of Ezechiel 26,7, he prophesied to the emperor the nonviolent taking of Sicily and admonished him to show moderation. The Capitulum Generale of the cistercians condemns Ioachim in 1192 for leaving Corazzo and orders him to return. Geoffrey of Auxerre, secretary of Saint Bernard, attacks him as a false prophet and hints at rumors about Jewish origins of Ioachim. 1194, 1195 and 1197 Henry VI, now in possession of Sicily, makes generous donations to S. Giovanni in Fiore. On Good Friday 1196 Ioachim is called to the court of Palermo as the confessor of the empress, Constance de Hauteville. The 25th of August 1196 pope Coelestinus III approves the monastic rule of the Ordo Florensis founded by Ioachim. 1198 Ioachim is in Rome, attending the conclave electing Innocence III. In 1200 both the Expositio and the Concordia are completed, and Ioachim submits them with all his works to the judgement of the pope. The 30th of March 1202 Ioachim dies at Petrafitta. He is buried in the church of S. Giovanni in Fiore. The inscription on his tomb reads: "Hic Abbas Floris/caelestis gratiae roris", meaning: Here [lies] the abbot of the flower/of the dew of heavenly grace.

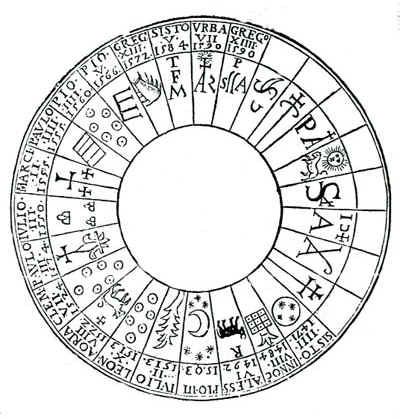

METHOD OF EXEGESIS - QUASI SIT ROTA IN MEDIO ROTAEI shall give only the basics of Ioachim's method here, enough to make a modern man's head swirl (wheels within wheels within wheels...), but not enough to drive the unprepared reader mad - I hope. From his life it can be derived easily that Ioachim must have been mostly self taught with material available to a southern Italian monk. We have no indication that Ioachim knew of Abelard's thoughts, and his knowledge of the Magister Sententiarum, Petrus Lombardus (whose summa was THE text book for doctorands in theology from 1150 on), was criticized by Saint Bonaventura as lacunary. He knew, however, books of the exponents of the school of Alexandria (Cassiodorus, Ticonius, Eucherius de Lyon) and of the school of Antiochia (Junilius Africanus, Adrianus), and he knew Augustine's De Doctrina Christiana and De Civitate Dei. For Ioachim, as for all clergy of his time, the goal of theology is exegesis, the proper understanding and use of the Holy Scripture. And this understanding is not the result of arguments, but of sudden insights, revealed by juxtaposition of events from the old and new testament, from past and present. His methods are the ones of the schools of Alexandria and Antiochia, typology and allegory, which he brings to a last subtlety. The traditional four senses of theological insights are given in a distich of Augustinus de Dacia: "Littera gesta docet, quid credas allegoria, Moralis quid agas, quo tendas anagogia." (The letter teaches the facts, allegory what to believe, morals teach how to act, anagogy where you will go.) Out of them Ioachim makes TWELVE senses (intelligentiae spirituales) in two groups (intellectus allegoricus and intellectus typicus). What each sense confers is illustrated by Ioachim himself on the example of Abraham's first and second wives, Agar and Sarah. The five senses of the intellectus allegoricus, concerned with the relation between letter and spirit of the Scripture, work thus: Intelligentia hystorica finds in Agar the servant and in Sarah the free woman. Intelligentia moralis finds in Agar the affection of the flesh, in Sarah spiritual attachment. Intelligentia tropologica finds in Agar the letter of the Holy Scripture, in Sarah its spiritual understanding. Intelligentia contemplativa finds in Agar the active life, in Sarah the contemplative one. Intelligentia anagogica finds in Agar the totality of present life, in Sarah the life of paradise to come. Intellectus typicus is concerned with the relations between diverse parts of the Scripture, and between the Scripture and the world. The seven senses of the intellectus typicus correspond to all possible relations between the three persons of the Trinity, and to the seven ages of history known since Augustine, but reworked completely by Ioachim to fit his eschatological worldview. So we have an intelligentia of the Father, of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, an intelligentia of the relation between Father and Son, Son and Spirit, Father and Spirit, and, at last, an intelligentia of the relation of the complete Trinity. This last intelligentia, for example, sees all priests as corresponding to the Father, all the church from its beginning to the end of history as corresponding to the Son, and the celestial Jerusalem as corresponding to the Holy Spirit - but also the relations of the Trinity are mirrored in the relations of priests, church and paradise. While such theological senses since Augustine were nearly exclusively used to find correspondences between the old and new Testament, Ioachim uses his enhanced repertoire of senses to find such correspondences, which he calls concordiae, among old Testament, new Testament and the present history. Of course his method is incommensurable with the scientific, argumentative approach of the Thomists at the end of the 13th century. It is, in fact, a different paradigm. Deductions drawn from the Holy Scripture the same way as from any other philosophical authority would have appalled Ioachim. (Aside: Can you imagine a Thomist tempering a divine aura? I can't. But I do imagine Ioachim in this field, turning any bishop's work inside out, upside down and being thanked for it.) About the justification of his method the Chronicum Anglicarum of Ralph of Coggeshall gives an answer. When questioned 1198 in Rome, Ioachim stated that he never received any prophecy (prophetia), prediction (conjectura) or revelation (revelatio), but that the Lord, "who one time gave to the prophets the spirit of prophecy (spiritum prophetiae), gifted me with the spirit of understanding (spiritum intelligentiae) to understand in all clarity, in the spirit of God, all the mysteries of the Holy Scripture, like the holy prophets understood them who one time wrote them down in the spirit of God." This was accepted until the last third of the 13th century.

THEOLOGY - PSALTERIUM DECEM CHORDARUMIt is very significant that Ioachim's contribution to theology in a literal sense, study of the nature of god, is a visualization, a symbol, and not a theory to be argued about. Whitsunday 1183 Ioachim saw in his mind the symbol of the Holy Trinity, a psalterium with ten chords. He explains how the triangular corpus of the instrument (corresponding to the Trinity) requires all three wedges (corresponding to the persons), how each wedge implies the other two to make the corpus, and how the corpus can be taken apart, but then ceases to be an instrument. On top of this he sees in the outer form of the psalterium the capital alpha, and in the hole in its center the capital omega, beginning and end of the alphabet and of the world Ap.1,8). Then he goes further to look at the small omega, which he sees as the circle breaking apart and revealing a comma, thereby being a symbol of the Holy Spirit coming from both the Father and the Son, and of the condition of the Holy Spirit, coming forth from the other two conditions.

DOMINANT SOCIAL PARADIGM - CONCORDIA TRIUM STATUUMIf there was ONE dominant SOCIAL paradigm governing medieval Europe around 1200, it had a very strong foundation in Augustine's De Civitate Dei and De Trinitate with their opposition against any millenarism and eschatology in time. These confirm that the sixth and last age of history has begun with the coming of Christ, that the church, as is, is the only way to salvation and that hence any possible development in time is of no importance for the general state of the world. Until the end of time there must be priests to guide the flock, kings and emperors to rule it and peasants to feed it. This world could in a socially acceptable way be renounced only by becoming a monk or, more radically, a hermit. Any other opposition was likely to be branded as heresy. Against this static worldview Ioachim puts his exegesis, transforming the present into a time as important as the time of Christ, promising the end of history in the near future, in the age of abundance of grace. According to his computation (supputatio), there will be 42 generations of 30 years each under the condition of the Son. This is, because Judith remained a widow for 42 month of 30 days each. From the last book of the new testament, the Apocalypse, he finds the signs to be observed at the end of this condition, reviving again the millenarism of the early Christians, though he does not predict the end of the world, but its final transformation. Ioachim left it to posterity to monitor the years until 1260 for the seven headed dragon, the antichrist and the lamb. As he had many followers, especially among the Franciscan order, his exegesis has in a very tangible way changed the dominant social paradigm of his time, until 1260. Afterwards the disappointment of many of his more simpleminded followers and upcoming scientific methods in theology undid most of his influence. "The true demolisher of Ioachim's method was Aristotle. ... [The rediscovery of Aristotle's philosophy] contributed to dissolve the identification of theology with exegesis. Under the influence of the Aristotelian concept of science the theologists were brought to admit in theory what they had a long time accepted in the practical application of their teaching. Theology is a 'speculative science'; it proceeds from revealed premises to new conclusions, just like any of the lesser sciences parts from undisputed principles. The theological method is argumentative, not exegetic. Finally the theologists reached the self-confidence which allowed them to leave the fiction behind, that all their work was a mere training for allegorical interpretation. Hence, after having formally freed theology from exegesis, they also freed the exegesis from theology." Beryl Smalley, 1952, The Study of the Bible in the Middle Ages, p.405ff (You guessed it: I translated it back from the Italian.)

REFERENCESNothing of this text is my own wisdom. I gathered it from: Andrea Tagliapietra: Il "Prisma" Gioachimita, Introduzione all' opera di Gioacchino da Fiore in Gioacchino da Fiore Sull'Apocalisse Feltrinelli Editori, 1994, ISBN 88-07-82089-7 (A Latin/Italian bilingual edition, I know of no translation) Henry Charles Lea: History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages. Harper & Brothers 1887 (Many, many translations into all languages)

Vaticini dal primo al decimo

Vaticino Primo

Acende Caluo, acciò non sij maggiormente decalvato, chè non dubiti di caluare la sposa, per nondrire la chioma dell'Orsa và, et pasci la Colomba con purissimi grani, che debbano essere della fiera prossima calpestati. Ma schiua che da sciocca pietà schernito, i grani infettati con quali pasci l'Orsa, non dij alla Colomba, che infettata dal cibo gravemente s'infermi, che tardio et con difficoltà si sanerà. Vaticino Secondo

Doppo la Luna ascenderà a Marte sitiente il sangue battisimale, et ascenderà dalla torre all'altissimo seggio, il quale offuscarà il chiarissimo Sole. Co'l Giglio et la Croce crociarà l'Aquila. A me non edificherai il tempio percioche sei huomo de i sangui, con zelo immoderato, e virtù simulata denigrando, e discipando le cose superflue, solo restringendo la pace, et diuorando tutte le cose. Vaticinio Terzo

Piglia supplantatore gli' eccelsi honore, arbore inutili, et infruttuoso, che pensi di fare cose grandi, essendo debile di mente, e di corpo, non potrai adempire le cose, che pensi, perche poco veggierai, presto dormirai, e non sorgerai sempre viuerai in tribolazione, ancorche poco. Vaticinio quarto

Ecco huomo della progenie di Scariotto, c' hà il principato occculto. Per il quale l'Agnelo rouina. Neronicamente regnando, morirai desolato, saranno abbreuiati que' giorni, il quale Tiranno terribile conturberà tutto'l mondo, ferisce il Gallo, lieua le piume all'Aquila. Il Gallo, e l'Aquila toglieranno à forza la superflua potenza di quello. La Colomba non temerà portando il ramo d'Oliua, facendo il nido ne' forami della pietra, la sicurtà della quale è nell'Angelo del testamento. Perchè tanto brami il principato Babilonico, ilqual non potrai ottenere? sorgerà contrà'l giusto, e lo legherà con legami. Vaticinio quinto

Dal minimo al grandissimo grado sei asceso misero Pianeta regnàdo dal Ciel stellato sei disceso nel baratro della vanità, lasciando la prima sposa vedova, guai, guai imprudente, et inutile, qual tutto sei occupato circa'l sozzo nodrimento di Venere, non pensi alla terra di benedizione da perdersi in parte per tua negligenza. Quando odi queste cose, piangi irrimediabilmente, percioche farà tribulatione tale, quale non è stata dal principio fin'hora. Quadratamente vincerai, et subito in Babilonia morirai. Sei huomo di morte, ma alcuni beni son stati trovati in te. Credi dunque al maggiore, et migliore di te perchè il Signore hà trasferito il tuo regno. Nell'oriente commotione, e dopo la commotione fuoco deuorante tutte le cose. Vaticinio sesto

Benedetto chi viene nel nome del Signore, contemplatore di tutte le cose celesti, qual semplice cauato fuori dalla terra tenebrosa ascende, e discende; percioche la voce gemina, et vulpina diuorerà il principato di quello, et tribolato in paese forestiero morirà. O quanto si dolerà la sposa della caduta del legittimo sposo, data ad esser diuorata al Leone. Perche ò semplice huomo, lasci la sposa ad esser data ad aspri cani abbaianti. Pensa al tuo nome, e fà le prime opere, acciò sij ricevuto nelle parti d'Oriente. Vaticinio settimo

Questo è l'uccello nerissimo di genere Coruino, che discipa l'opere nere di Nerone, subito morirà nella terra petrosa, quando vedrà il frutto bello, suaue à mangiare, all'hora nutrirà in gemma, chi gli ministrerà il principio della morte. Vaticinio ottavo

Vedi quì lo sposo della donna Babilonica, che fugge la sua sposa à fe abominabile quasi vedovata lasciandola. Il nome di quello dissone crudele, immondo, ingiusto, che manca di virtù, desideroso della vanità immoderatamente, che rallenta le chiaui. Corrittore, Gladiatore, che congrega, e corrompe le lucidissime stelle. Qual perderà lo splendore contrà'l Sole tenebroso. Finalmente essendo per combattere la Luna lo perseguiterà, cascherà da alto, et oscurerà le cose eccelse. Vaticinio nono

Da infima generazione, ascenderà una sanguinosa bestia prima, et nouissima, che crudelmente diuorerà il minimo figliuolo, et innocente. Uno sei, e non hai eguale à sparger' il sangue innocente. Perciò nel tuo tempo sorgerà un falso Profeta, e sedurrà molti. Percioche con i tuoi mali hai crudelissimamente ferito il mansuetissimo Agnello, ponendo la tua bocca contra Christo Signore, oscurando le Stelle del Cielo, la tua malizia ti ministrarà vergogna, il quale sei solo gratioso di nome. Vaticinio decimo

Da borghi montuosi, et sodi dalla terra candida ascenderà unì huomo facendo atti singolari, in parte farà lucide, et oscure le Stelle; ma non leuarà gli eccelsi, che la predetta bestia hà offuscato mà restarà l'Agnello gravemente ferito. Poche cose spargerà, molte congregherà, bisognoso morirà, et mancherà à a'ì sepoltura propria. La Colomba perseguiterà il Coruo regnerà tutto solo, tutto d'altrui, lasciando vedoue molte spose.

Vaticini dall'undicesimo al ventesimo

Vaticinio undicesimo

Acenderà alle cose alte preuenuto da doppia benedittione l'amator del Crocifisso, cultor della pace, alto d'ingeno: mà non adempirà le cose, ch' egli pensa. Caderanno le cose alte, sublimerà le infime, ornerà il Cielo, saranno tagliati i boschi, distendendo le mani ai poveri, sposerà le vedoue. Et all'hora guardati sfera volubile, e nera, che non sij impedita dal vento d'Aquilone nella tribulatione, difenditi con la Croce. Vaticinio dodicesimo

Acenderà questo huomo à doppi honori, venendo dal centro nuuioloso, concordando i discordanti, rivolgendo la Luna, portando in mano il rasoio per tagliare via le cose souerchie, mangierà le carni arrostite, et berrà vino mirrhato entrando pouero, considerando cose alte, alle infime condescendendo. Vaticinio tredicesimo

A cose alte sei chiamato, òPrincipe canuto di mente, che stai in pene? Sorgi, et sij robusto, uccidi Nerone, e farai securo; sana i feriti, prendi il ventaglio, ammazza le mosche, scaccia i vendenti dal Tempio, annuncia il giusto, schifa i circoncisi, indirizza la Colomba raffrena gli assetati. Vaticinio quattordicesimo

E divenuto oscuro l'oro, e mutato il bonissimo colore, la rugine ti consumerà, hai trovato dolce principiosa à fine tribulante, il primo guai è partito, et ecco il secondo guai, fuggiamo dalla sua faccia. Grida con fortezza, perchè hormai incominciano gli ultimi crucci. Ah, ah, doue à Lucifero? doue sono andate le Stelle? Corriamo, e non riguardiamo indietro, perchè dall'Aquilone si manifesterà ogni male. Prego, Signor mio manda quello, che hai da mandare. Vaticinio quindicesimo

Questa è l'ultima fiera, terribile di aspetto, che tirarà giù le Stelle, all'hora fuggiranno gli uccelli, e solamente i reptili resteranno. Fiera crudele, che consumi tutte le cose, l'inferno t'aspetta. Potente il Signore à mutare il suo proposito, perchè nelle sue mani sono tutte le Stelle del Cielo. Finiscono le rivelazioni del Beato Gioachino Abbate del Monasterio Florense in Calabria, e seguono quelle d'Anselmo Vescovo di Marsico. Vaticinio sedicesimo

La generatione scellerata, l'Orsa che pasce i Cagnuoli, et in cinque conturbanti i scettri di Roma, noua, et in XXXVI, anni miseramente caminarà. Il primo fine della setta, che hà cinque figliuoli, percioche dalle figure è il mondo. La Città Metallica hancora riceuerà medesimamente i Barbari. Ma quando vederai l'Orsa madre dè Cani miserabilmente piangi nell'altezza del Cielo, acciò consegui l'agiuto da Dio. Molti ingannerai sceleratissimo, sotto l'altrui pelle; percioche cambiata volgi il fallace vedere in terra ascendendo, et facendo inganno in molte cose. Vaticinio diciasettesimo

Il secondo figlio, un' altra Fiera volante, Serpente al mezo giorno, ligato grande, et nero tutto priuato di lume da' Corui, manifestando il tempo delle figure literali, qual succede al fine paterno, essendo Serpente misero, et distruttione dell'Orsa. O come sei e sia dei miseri Corui, essendo abhominabile generatione loro. Dall'Oriente miserabilmente sarai turbato, te medesimo somigliante della Città lume delle genti darai nel tempo della paura. Vaticinio diciottesimo

Il doppio terzo, et l'uccello, che porta la Croce, il cauallo portatore di corno, così molto veloce, come pronto, e lasciuo, hauendo principio l'unità, et il fine all'unità doppia, della vacanza prima della recurua figura dei numeri l'estremo, nel tempo come nel buon anno. Viene il giorno, nel quale tenirà la metà della curua figura, molto certamente grande Re de gli uccelli del Sole. Percioche questo riceuendo il principio dal mezo giorno, nel quale empirà nel giorno cornuto mediante la Stella del Polo nella sera, et punito come essendo molto veloce, et preparato alle guerre, ò generazione di Bizantio, che hai gli oditi a noi inclinati, legni senza frutti. O amico ma l'ultima syllaba la ferità guadagnerà te nei luoghi acquosi fuor di speranza cadendo in te, il principio, e'l fine del Coruo. Vaticinio diciannovesimo

Qvesto Collaterale quarto dall'Orsa, che manca di coltelli, et homo, che muoue il taglio della rosa: non di meno si seccherà come rosa, et tagliando la rosa per tre anni morto; percioche la terza lettera, et il terzo elemento della cosa vede. Peroche riceuendo il principio acciò taglisse il fiore, non hauerà misericordia di te, ancor stij nel principato. Vedi, inperoche quello incomincia raccorre la rosa, portando innanzi ne gli huomini hauendo il fine, nel quale allegrati molto in vano. Vaticinio ventesimo

Vedi un'altra fiata l'alienno, di chi è la falce grande, et la rosa, qual porta il terzo innanzi duplicato del primo Elemento sono diuisi. Medesimamente congionti del portator della falce di quattro mietiture, scriuo, sarà S. Mà ogni Principato, qual hai consumato co'l coltello nei tempij de gl'i doli, doppo poco resuscitarai, tre anni nel mondo viuerai, vecchio grandamente nell'infimo con doi tribulationi nel mezzo caderai.

Vaticini dal ventunesimo al trentesimo

Vaticinio ventunesimo

Ma la vacca il quinto, et il fine pascendo gli Orsi manifesta i segni, et il luogo, onde venendo solo à me manifesterai gli amici, primi hai le virtù de glialtri, più dispensi circa gli amici, perciò hai trouato dolcissimo fine. Solo sarai sublimato dalla gloria, et morti lasciarai potentissimamète le potenze, peroche come la pioggia ben trouerai.

Vaticinio ventiduesimo

Vn' altra Orsa pascente i Cagnuoli, et in tutte le cose fuor che nell'ombra solamente scritta simile natura dè tempij. La natiuità abhortiua innannzi figura. Percioche nell'ultima sono scritte l'ultime subsolari innanzi, et in dietro le corone manifestanti la diuisione di tutta la penitenza.

Vaticinio ventitreesimo

Gvai, guai Città misera, che sostenni dolori, affanni, et passioni. Percioche la Città acciò apparisca il compassioneuole lume da quì a poco tenirà l'armi piccio tempo. Occisioni faranno in te, et spargimento de' sangui. La onde un' incomincinando non mancheranno in cinque principati della tua Monarchia. I Draconi sprezzeranno l'uomo. Quali hanno mangiati come cibo, à pezzo à pezzo straciaranno i membri suoi non tagliati, et a pugna intestina eccitati innumerabil moltitudine tagliaranno con la spada à migliara sei sette numerati et ogni Ditta sarà multiplicata alla fornicatione, e cederà il macchiato, l'adultero, il rapitore, l'ingiusto, il Sodomita vedrà l'ultimo lume innanzi gli occhi M. di quello.

Vaticinio ventiquattresimo

Hai figurato l'amicitia Volpina patientemente raffrenando il senso, come molto vecchio, et c'hà il senso canuto, ma li piaceri che veniuano doppiamente, et sette siate il piacere hai lasciato sprezzarsi l'uno l'altro, et nel spargimento della valle de i sangui spargersi. Tu per la vittoria hai distese le mani. Bene, e gloriosamente hai ricevuto il pallio nel fine del Scettro.

Vaticinio venticinquesimo

Guai à te Città di sette colli quando la lettera K sarà laudata nelle tue muraglie. All' hora s'aucinerà la caduta et destruttione dei tuoi potenti, et giudicanti l'ingiustitia. Chi hà i suoi diti à quisa di falce, chi è falce, dell'abbandonare, et nell'altissimo hà bestemiato. Ysatios Citopam dell'occisione del sangue. Giouanni buona gratia, Constantino pouero. Vedi tu, che consideri le cose sante, et le porti sopra le spalle, che la tua poluere non sia in obbrobrio, et la barba profonda giustamente tagliarà, et grandemente sarai vituperato tu Consigliero nella morte del Pontefice, il cui nome. Io. Obi.

Vaticinio ventiseiesimo

Et satà eleuato l'unto, che hà il pronome del Monacho habitando la pietra di fuora è venuto à me aliena lasciando i pianti, et il viuere agresti dell'una motto, e gemendo congregando beni, dissipando ogni premio d'iniquità qual tutto giustificato quando la Stella apparirà nera, all'hora sarai nudo medesimamente molto ne gl'interiori della terra.

Vaticinio ventisettesimo

Morto et hora smenteicato al petto, conoscono molti, ancorche niuno costui veda della Deità manifestato fuor di speranza tenirà i scettri di questo Imperio. Percioche parimente manifestato in Cielo il precone invisibile tre siate grandamente gridarà. Andate con prestezza all'occidente della Città de i sette colli, trouerete un'huomo habitatore amico mio, portate questo nelle Regali sedie, caluno, mansueto, piaceuole, di alta mente, acutissimo principalmente à vedere le cose future. In te hauerai l'imperio della Città de i sette colli.

Vaticinio ventottesimo

Ecco similmente l'huomo del primo genere nascosto, entrando primieramente singolare ne gli anni numerosi. Nudamente è venuto dalla pietra tenebrosa acciò incominci la seconda splendente vita. Imagine verissima della seconda vita tanto sodamente sodo de gli anni duplicati entrerà la pietra.

Vaticinio ventinovesimo

Prendi la cidarai monda in te commessa, et vestiti sopra di nuovi vestimenti vecchio di sentimento, Sacerdote grande di Dio, non sij pregosmà riceui potentissimamente, pensa del fine, et al bene derizza la portatrice del Scettro, altre cose certo non temendo. Percioche di sopra hai ricevuto questo tempo solo con tre aurore gli anni circondati, et con l'undenario delle Stelle compiuto, finalmente ad un fine sacrato, quello di che fai marauiglia hai lasciato placidamente, hai placato l'altercatione segui la uocatione alla presente gloria bene sei uenuto. Mà à i principij disse. Bene finisci tutta la cultura, et camina le celesti habitationi. Percioche nel celeste è il principio, et il fine.

Vaticinio trentesimo

Hai ritrouato la buona vita dall'ingloriatione, mà dalla virtù hai ricevuto più, che dalla fortuna, mà non guadagnerai la virtuosa gratia. Percioche per l'inuidia ti accaderanno giudicij nocenti, non sarai privato dalla sorte di sopra. Guai Città de i sangui tutta piena del straccio della buggia, non si partirà da te la rapina, la voce del flagello, la voce dell'impeto della ruota, e del cavallo fremente. Il cor di fiera sia dato à lui, et sette tempi sian mutati sopra lui. il cor di quello dell'abominatione sia cambiato.

INTERPRETAREA CA METODA EXEGETICA. UTOPIA CONCORDANTELOR LA GIOACCHINO DA FIORE Brindusa PALADE Abstract First, I tried to present here some fundamental features of the interpretation of text, a philological technique with ancient origins that will be developed by the Christian exegesis. After a small historic approach, I stressed a "new" method of interpretation, different from the traditional exegesis of the Bible and especially from the four sensus of the sacred book. This new exegetical method, called the "concordia", legitimates a spiritual process developed into the secular history and, therefore, supports a "radical eschatology". Certain authors claimed critically that the concordia established a kind of theological confusion, turning over the Christian hope for a transcendent <plenitudo>. Finally, I exposed the direct critique of the Aquinas versus Joachim's history of salvation, that is, the reaction the Scholastic authority had toward the original interpretation of Joachim of Flore. The theological reasons for these critiques are the „dangerous" mirages promoted by Joachim's exegesis. A interpreta un text inseamna a opera explicativ asupra registrelor sale semantice, a ,media intelegerea"1 sa, capturind cifrul care-l disimuleaza, a traversa, cu rigorile canonice ale artei interpretarii, un spatiu lingvistic incarcat de simboluri si de echivoc. Textul destinat interpretarii are o dimensiune verticala, o stratificare semantica ocultata si, simultan, o expresie orizontala: suprafata lingvistica a textului. Interpretarea presupune asadar actualizarea etajelor de semnificatie ale textului prin studiul atent al suprafetei sale orizontale. Pentru aceasta, insa, este necesara interventia unui interpret calificat.2 In pofida normelor doctrinale ale exegezei, jocul interpretarii presupune prin natura sa polisemia, interpretul neputind furniza, in cheia sa interpretativa, o lectura ultima si definitiva. Orice monopol care instituie o ,tiranie a interpretarii"3 risca sa incalce regulile care garanteaza autenticitatea jocului, tradind prin constringerea la univoc misterul semantic ce investeste scrierea cu insemnele unui ritual nevazut. Pentru exegeza teologica, justificarea unei interpretari univoce care sa atenteze la diversitatea constitutiva a oricarui demers hermeneutic a fost insa fermentul vital ce a animat, timp de doua mii de ani, disputele cele mai inversunate si a intretinut insasi „istoria Bisericii"4. Pe de alta parte, demersul interpretativ comporta constiinta unei departari, unei distante temporale pe care interpretul incearca sa o parcurga retrospectiv, aparind ca produsul „constiintei unei rupturi cu trecutul"5. Interpretarea presupune incercarea de a elucida textul pe coordonatele unui timp coextensiv inteligibilitatii sale: decriptarea textului nu se face decit in prelungirea unui registru de semnificatii reconstruit, ce proiecteaza gindirea interpretului in ,climatul" de idei propriu unei epoci trecute. In epoca elenista, Scoala din Alexandria, predominant filologica, a pus bazele unei tehnici interpretative ce opera prin explicarea textelor fiecarui autor clasic, furnizind referinte la corpus-ul scrierilor sale. Aceasta s-a numit metoda istorico-gramaticala. Alternativa a fost interpretarea alegorica, practicata de Scoala de la Pergam, a doua mare scoala filologica a antichitatii. Metoda alegorica avea o filiatie mult mai veche, fiind practicata anterior de retori, de sofisti si, mai tirziu, de stoici. Etimologic, a aplica metoda alegorica, inseamna „a utiliza termeni diferiti (de cei proprii)"6. Alegoria este o figura retorica destinata ,sa spuna altceva decit ceea ce semnifica"7. O prima varianta de aplicare a metodei alegorice pentru o hermeneutica de tip religios este cea a lui Theagenes din Rhegium, care, probabil stimulat de atacurile lui Xenofan, a propus o lectura alegorica a mitologiei grecesti, incercind sa justifice comportamentul libertin si irascibil al zeilor din Panteonul homeric8. Evolutia metodei alegorice pare acompaniata subtil de prezenta unei „umbre" tematice subterane, „la fel de veche ca si gindirea insasi"9, care urca pe firul traditiei de la astrologia chaldeeana si orfism, pina la neoplatonici si Sf. Augustin: tema invelisurilor corporale ale anima-ei. Sf. Augustin, atras de metoda alegorica, nu putea sa ignore simbolismul neoplatonician al invelisurilor, ale carui urme sint vizibil prezente in comentariile sale: tema cerurilor care ,pier ca un vesmint"10, de filiatie orfica, e reluata de neoplatonici sub forma „mantiei cosmice"; si a cerului ca peplum al zeilor. Aceasta ,moarte" a invelisurilor corporale semnifica alegoric, la Sf. Augustin la fel ca si la Porfir, ,dezgolirea" purificatoare de invelisurile vizibile si invizibile, asceza prin care se renunta la invelisul pasional ce obtureaza accesul anima-ei la ,patria sa originara"11. In exegeza biblica se opereaza, in fapt, cu acelasi aparat simbolic: textul este ,dezgolit de tot ce e strain de Dumnezeu"12, interpretarea fiind doar mijlocul ce restituie textului sensul cu care a fost investit initial, incifrat deseori alegoric in referinte profane. Regia interpretativa a polisemiei textului religios, in care alegoria este numai unul din ,cele patru sensuri ale Scripturii"13 pare ca se modifica o data cu aparitia abatelui calabrez Gioacchino da Fiore, personaj care a suscitat multe controverse in epoca. El nu respinge „sensurile"; traditionale, ci doar opereaza unele modificari. Printre altele, el introduce in lectura textului sacru un sensus ulterior, a carui noutate, in aplicatiile sale predictive, este absoluta: e vorba de asa-numita concordia (care, dupa unii autori, ar substitui aproape integral metoda alegorica). Aceasta intelligentia14 instituie in fapt o noua metoda exegetica, a carei investitura profetica a fost cauza principala a acuzatiilor vehemente din epoca: Gioacchino a fost invinuit de deturnarea mundana a eshatologiei printr-o „historia salutis"15 si de ,transformarea sperantei in utopie"16. El propune, in fapt, o lectura a Noului Testament ca o actualizare prin concordanta cu ,figurile" veterotestamentare (ceea ce, in virtutea unei sub-specii a alegoriei in verbis, care s-a numit allegoria in facto17 si, ulterior, ,tipologie", adica prefigurare a personajelor si evenimentelor din Noul Testament prin figuri sau tipuri veterotestamentare, nu constituia ceva inedit). Numai ca, Gioacchino considera ca, daca acest lucru este posibil, se poate merge si mai departe: Noul Testament, la rindul lui, ar putea fi citit in cheia concordismului, ca „o prefigurare a unei epoci viitoare" o epoca a „Spiritului", care ar reprezenta culminatia celor doua etape premergatoare, fiind o „lenitudine" mundana fara precedent in istorie. Ideea istoriei salutare, spun comentatorii lui Gioacchino, poate fi regasita intr-o forma aproape integrala in hegelianism18, printr-un curent de idei misterios care se propaga prin ,istoria influentelor"19 (Wirkungsgeschichte), fara ca in idealismul speculativ sa fie sustinuta, asa cum se intimpla la ,precursorul" sau „calabrez, de o metoda fondata pe calcule matematice, nutrita de suflul prevestirii unei teofanii. S-a vorbit, cu toate acestea, de un „Hegel secret"20, care invoca, intr-o scrisoare catre Schelling, ideea, propagata deja de Lessing, a unei „Biserici invizibile"21. Sistemul hermeneutic al lui Gioacchino este de o ,cerebralitate extrema"22, desi textul propriu-zis, fondat pe increderea in „principiul sau regulator" (concordia)23 e plin de forta expresiva, permitindu-si evaziunea din granitele istorico-literale schematice intr-o Weltanschauung aproape mistica, impregnata de o fantezie care respira, structural, in crescendo-ul celor trei epoci gioachimite24. Avem de-a face, pe de-o parte, cu un sistem interpretativ riguros, fondat pe criterii „stiintifice" si, pe de alta parte, cu o metoda care isi revendica obirsia „mistica" (concordia i-ar fi fost revelata lui Gioacchino pe durata unei iluminari, cum marturiseste intr-un text faimos: et tota percepta veteris ac novi testamenti concordia revelatio facta est25).Henry Mottu distinge patru registre de semnificatie ale concordiei: 1. concordia sau concordanta inteleasa ca o armonie a textelor, intr-o forma „sinoptica"; 2. paralelismul figurilor, evenimentelor, aliantelor si locurilor geografice dintre cele doua Testamente, in sensul unei similitudini; 3. ,conformitatea structurala" (sesizata de Grundmann) a diferitelor perioade istorice, printr-o metoda corelativa; 4. concordia ca regula de compensatie. Pe scurt, concordia ar fi o metoda de „a extrapola din aproape in aproape un viitor ale carui linii de forta s-ar gasi, crede Gioacchino, intr-o potentialitate totala in textul scriptural"26. In plus, intervine aici, in chiar economia interpretarii, un element care modifica intreaga perspectiva: textul aluneca, aproape insesizabil, in celalalt text, cu care trebuie suprapus semantic. Concordanta nu mai presupune aici o „interpretare", ci o „transinterpretare"27, textul dobindind un soi de transparenta prin care interpretul trebuie sa intrevada celalalt text. Coerenta analogica prin care Gioacchino vrea sa extraga logica viitorului din cea a trecutului intimpina insa dificultati, atunci cind se risca o interpretare care implica actiunea gratiei: criticii sai au comentat ironic pretentia sa de a dovedi per concordiam „ca atita timp cit va dura legea circumciziei, care a fost data la inceput doar sub forma unui comandament si ulterior confirmata scriptural, tot atit va dura si gratia Evangheliei"28. Dintre criticile si contestarile aduse interpretarii gioachimite, retinem aici observatiile facute, de pe pozitiile scolasticii, de catre reprezentantul sau cel mai prestigios, Sf. Toma din Aquino. In Sent IV, d. 43, q. 1, art. 3, Sf. Toma ia pozitie impotriva ideii unei prefigurari a Noului Testament de catre Vechea Scriptura. Exista, spune Sf. Toma, evenimente esentiale care scapa unei asemenea interpretari (cum ar fi episodul Invierii), ceea ce compromite exactitatea unei analogii metodologice. Pe de alta parte, o data cu venirea lui Hristos, multe din ,figurile" veterotestamentare si-ar fi dobindit deja implinirea, orice inaintare interpretativa fiind, de acum inainte, ipotetica.29 Ceea ce e echivalent cu a spune ca, pe de-o parte, Sf. Toma submineaza exegeza gioachimita in planul metodei (amendind, o data cu inexactitatea concordantelor, si literalismul excesiv al textelor gioachimite) iar, pe de alta parte, marcheaza precaritatea sa in plan teologic: Gioacchino nu dezvolta o viziune hristocentrica, rolul lui Hristos fiind limitat la durata unei perioade istorice si neesential in economia mintuirii. O alta corectie adusa de Sf. Toma sistemului hermeneutic gioachimit se refera la confuzia intre ,lucrurile semnificate", res significatas, si modurile de semnificare, modi significandi, derivata din absenta unei distinctii clare (nu doar conceptuale, ci si functionale) intre modi essendi si modi significandi30. Gioacchino nu identifica intotdeauna precis modurile de semnificare, ceea ce, afirma Sf. Toma, ar atrage dupa sine inexactitatea si lipsa de discernamint in stabilirea concordantelor intre doua figuri ontologic ireductibile (Sf. Toma foloseste exemplul concordantei gioachimite dintre Isaac si Iisus Hristos, pe baza „neasemanarii", dissimilitudo, dintre „generarea dupa carne" si „generarea dupa spirit", care ar furniza, dupa Gioacchino, un criteriu suficient pentru stabilirea unei analogii intre modi essendi). Critica tomista nu se vrea insa inexorabila, tinzind numai sa reduca interpretarile lui Gioacchino la un orizont mai realist31. Pe de alta parte, desi Sf. Toma cunostea direct textele lui Gioacchino, fara sa-i atribuie eronat (asa cum s-a facut ulterior) texte care nu-i apartineau, este posibil ca, in lectura sa, sa fi operat cu propriile sale „sensuri" asupra expresiilor lui Gioacchino32. Astfel, modul in care cele doua Testamente decurgeau unul din celalalt, printr-un soi de filiatie simbolica progresiva, pare a fi dificil de inteles pentru cineva care nu concepe istoria decit in sensul unui flux liniar de evenimente, in care locul central il ocupa intotdeauna Hristos. Iar ideea gioachimita a „plenitudinii" si „soteriologiei" terestre nu poate avea nici o consistenta pentru Sf. Toma, intrucit, pentru el, legea evanghelica insemna ultima perfectiune (terestra) posibila, inaintea unei eshatologii autentice33. Paradoxul final ar fi ca, daca evolutia sperantei eshatologice a fost deturnata in utopie, cum spune De Lubac despre exegeza lui Gioacchino (intr-un mod poate prea radical), resortul unui atare mesaj, intr-o epoca in care biserica, imperiul si provinciile autonome se hartuiau permanent, a fost cu siguranta religios, concentrat impotriva ,mundanitatii" lumii si bisericii34. In final insa, intentia spirituala care a legitimat eshatologia terestra a fost ea insasi deturnata, secularizarea lumii fiind sprijinita subteran pe o hermeneutica spiritualista pe care istoria insasi (ca o ironie a cercului hermeneutic) a infirmat-o Bibliografie selectiva Francesco D'Elia, Struttura del linguaggio gioachimita, in ATTI del I Congresso internazionale di studi gioachimiti. Maurizio Ferraris, Storia dell'ermeneutica, Milano, Bompiani, 1992. Y. D. G‚linas, La critique de Thomas d'Aquin sur l'exegese de Joachim de Flore, in CONGRESSO Internazionale „Tommaso d'Aquino nel suo settimo Centenario", Roma-Napoli, 1974. Mario Gigante, San Tommaso e la storia della salvezza. La polemica con Gioacchino da Fiore, Salerno, 1986. Henri de Lubac, Exegese medievale. Les quatre sens de l'Ecriture, vol IV, Paris, 1959-1964. Henry Mottu, La manifestation de l'Esprit selon Joachim de Flore, Neuchitel-Paris, 1977. Jean Pepin, La tradition de l'allegorie de Philon d'Alexandrie a Dante, vol. II, Paris, 1987. Beryl Smalley, The study of the Bible in the Middle Age, Oxford, 1952. Milton Terry, Biblical Hermeneutics, N. Y., 1883. Note 1.Cf. apud G. Ebeling. 2. Vezi Milton Terry, Biblical Hermeneutics, New York, 1883, despre calificarile canonice ale exegetului. 3. L. Pareyson, Originarieta' dell'interpretazione, in Hermeneutik und Dialektik, vol. II, Tuebingen, 1970, pp. 353-366; „tirania interpretarii" se refera aici la pretentia absurda si ilegitima de a confisca, in univocul unei interpretari, multitudinea tuturor formularilor posibile. 4. Apud G. Ebeling, Kirchengeschichte als Gescichte der Auslegung der Heiligen Schrift, 1947, p. 22: „Istoria Bisericii este istoria interpretarii Sfintei Scripturi". 5. Cf. H.-G. Gadamer. 6. Cf. Dictionnaire Etymologique de la Langue Francaise, par Oscar Bloch et W. von Wartburg, p. 19. 7. Heraclit, Quaest. homer. V, 2. 8. Vezi M. Ferraris, Storia dell'ermeneutica (1.1.3.) si J. Pepin, Mythe et allegorie. Les origines grecques et les contestations, pp. 97-98. 9 J. Pepin, La tradition de l'allegorie de Philon d'Alexandre a Dante, p. 137. 10 Op. cit., p. 138, apud Enarratio in psalm., 101, II, 14, P. L., 37, 1314: „Sed numquid etiam caeli peribunt? An secundum quemdam modum peribunt? Secundum quem modum? Secundum vestimentum" 11. Op. cit., p. 138. 12.Op. cit., p. 139.13 H. de Lubac, Exegese medievale. Les quatre sens de l'Ecriture (cele patru sensuri clasice sint: literal sau istoric, alegoric sau tipologic, moral sau tropologic si anagogic). 14 Termenul intelligentia este folosit de traditia exegezei medievale ca sinonim cu sensus sau cu intellectus, desemnind modul de intelegere a unui text si continutul acestei comprehensiuni. 15 Vezi M. Gigante, San Tommaso e la storia della salvezza. La polemica con Gioacchino da Fiore, Salerno, 1986. 16. H. de Lubac, op. cit. 17. Cf. Sf. Augustin, De Trinitate, XV 9, 15: „ubi allegoriam nominavit Apostolus (Gal., 4, 24), non in verbis eam reperit, sed in facto, cum e duobus filiis Abrahae, uno de ancilla, altero de libera, quod non dictum, sed etiam factum fuit, duo Testamenta intellegenda monstraret".Sf. Augustin comenteaza aici interpretarea pauliniana a celor doua figuri din Vechiul Testament, fiii lui Avraam, dintre care unul (fiul sclavei) ar simboliza Vechiul Testament pe cind celalalt (fiul femeii libere) ar prefigura Noul Testament. Aceste figuri care indica cele doua Testamente ar reprezenta o allegoria in facto, adica o forma de „tipologie" avant la lettre. 18. Vezi Henri de Lubac, La posterite spirituelle de Joachim de Flore. 19. Am optat pentru traducerea lui Wirkungsgeschichte prin ,istoria influentelor" si nu prin ,istoria efectelor", asa cum se face indeobste, considerind ca prima varianta este mai expresiva, surprinzind mai bine sensul pe care Gadamer pare a-l sugera. 20 Cf. trad. rom. a lui J. D'Hondt, Hegel secret, Iasi, 1995. 21 Op. cit., p. 302. 22 H. Mottu, La manifestation de l'Esprit selon Joachim de Flore... 23. Op. cit., p. 98.24 „Primus ergo status in scientia fuit; secundus in potestate sapientiae; tertius in plenitudine intellectus. Primus in servitute servili; secundus in servitute filiali; tertius in libertate. Primus in flagellis; secundus in actione; tertius in contemplatione. Primus in timore, secundus in fide; tertius in charitate. Primus status servorum est, secundus liberorum; tertius amicorum. Primus senum, secundus juvenem; tertius puerorum. Primus in luce siderum; secundus in aurora, tertius in perfecto die. Primus in hieme; secundus in exordio veris; tertius in aestate (_) Primus aquam; secundus vinum; tertius oleum."Apud Concordia, V, c. 84. 25 Idem, Pref., E 39bc. 26 H. Mottu , op. cit., p. 120. 27. Op. cit., p. 98. 28. Op. cit., p. 121. 29. Cf. M. Gigante, San Tommaso e la storia della salvezza. La polemica con Gioacchino da Fiore, Salerno, 1986. 30. Cf. Sf. Toma de Aquino, Summa theologiae; distinctia este studiata amplu de Heidegger in teza sa de doctorat despre modurile de semnificare (modi significandi) la Pseudo-Duns Scotus. 31. Cf. apud, B. Mcginn, The abbot and the doctors; scholastic reactions to the radical eshatology of Joachim of Flore. 32. Cf. Y.D. Gelinas, La critique de Thomas d'Aquin sur l'exegese de Joachim de Flore, p. 374:„Il faut remarquer d'abord que Thomas aborde l'exegese a travers ses propres perceptions". 33 Op. cit., p. 374.34 Apud, K. Loewith, Meaning and History, p. 158-159.

|

|